If there is something you really want to do, but you’re not doing it, there is probably another part of you that’s resisting. So it’s a negotiation between two parties, except that they are both you. They’re different parts of self, with needs that don’t seem to fit together—or not at the very same instant. The part that wants instant gratification, now and forever, is probably a lot younger than the part that’s more interested in getting valuable things done (like pursuing justice, or doing the laundry,), even if that means having to wait awhile for some of the other kinds of value (like ice cream, or a movie).

Read MorePeople have an evolved need to be part of something – to belong to a family that belongs to a tribe. Anyone who doesn’t have that can become susceptible to whatever offers itself as a substitute, even if the eventual price of belonging is unclear at the outset, and turns out to be too high. We are a profoundly social species, and the more isolated somebody is, the greater their risk for getting absorbed into a company that has cult-like features—especially if these only become obvious after some time has passed, and ties have been formed.

Read MoreIn F. Scott Fitzgerald’s great American novel The Great Gatsby, a self-made millionaire aspires to win the heart of a woman he once loved. Daisy is married and unavailable, but Gatsby has idealized her for years. He knows that she appreciates the outward signs of wealth, fame, and power—things that confer status—so he reinvents himself as a wealthy tycoon, hoping this will impress her enough to make her value him. But if it all works out, and Daisy is won over by glitz and bling, how will he know she really loves him? Gatsby is a man, not a Rolls Royce or a bank account.

Read MoreThe teaching frame of mind, the Teacher role, can take you out of your ego-driven worry about how you’re being perceived, because it helps you to focus on the material at hand and the communication process. Value judgments and the fear of embarrassment, imaginary comparisons of yourself to others, worry about rejection or failure—these should be crowded-out by the enjoyable business of sharing what you know. One of the best indicators of your likely success is that the interview was fun.

Read MoreIf I am stuck in the bitterness of feeling screwed-over, I may be living inside the misconception that any progress I dare to make would be a betrayal of the wounded child inside me. Adults boycott their own lives, they flounder and self-sabotage and procrastinate, because of a beautiful, bittersweet, tragic loyalty to their own grievances from long, long ago. The unwritten law of such a life is: If I go ahead and start building my own life for myself, it will mean that I approve of all the wrongs that were done to me in the past.

Read MoreImagine yourself one year in the future. You’ve now made about a hundred more remarks concerning your partner’s spending habits, their specific purchases, and their ideas about money, remarks that sprang from your anxiety and impulsivity. You rationalized your behavior by focusing exclusively on the fact that the money you were trying to save is, ultimately, for the both of you. But now, one year on, you can plainly see how much accumulated suffering this has caused, how much distance it has put between you and the other(s) whom you love. You wish you had a time machine, to undo the piteous waste of closeness and harmony that you squandered in all that worrying. Well, here you are, back in the present, with those twelve months still stretching out ahead, unspoiled by any thoughtless utterance or grim withholding. How will you use this second chance?

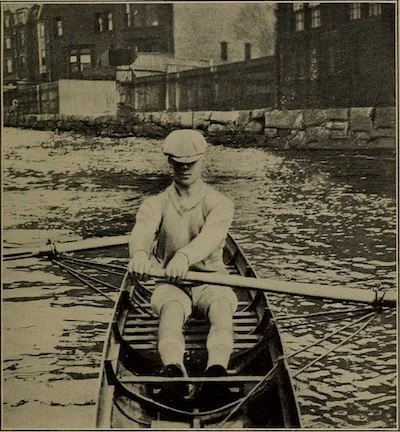

Read MoreI had a teacher years ago—a brilliant, soulful teacher of Ancient Greek, the late Jack Collins—whose maxim was “To row is human; to sail, divine.” Of course it was a play on the old proverb “To err is human; to forgive, divine.” What he meant was that there’s a place for discipline, and it’s often necessary, especially near the beginning of a project. But after discipline has done its work, after it’s gotten us launched, rowing our boat away from land, pushing on the oars, there comes a time when discipline is no longer needed, and the serious joy of the work takes its place.

Read More