If there is something you really want to do, but you’re not doing it, there is probably another part of you that’s resisting. So it’s a negotiation between two parties, except that they are both you. They’re different parts of self, with needs that don’t seem to fit together—or not at the very same instant. The part that wants instant gratification, now and forever, is probably a lot younger than the part that’s more interested in getting valuable things done (like pursuing justice, or doing the laundry,), even if that means having to wait awhile for some of the other kinds of value (like ice cream, or a movie).

Read MoreIf I am stuck in the bitterness of feeling screwed-over, I may be living inside the misconception that any progress I dare to make would be a betrayal of the wounded child inside me. Adults boycott their own lives, they flounder and self-sabotage and procrastinate, because of a beautiful, bittersweet, tragic loyalty to their own grievances from long, long ago. The unwritten law of such a life is: If I go ahead and start building my own life for myself, it will mean that I approve of all the wrongs that were done to me in the past.

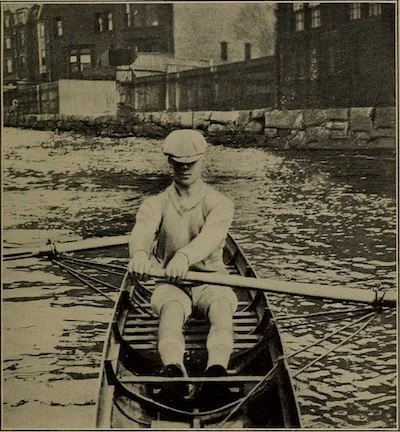

Read MoreI had a teacher years ago—a brilliant, soulful teacher of Ancient Greek, the late Jack Collins—whose maxim was “To row is human; to sail, divine.” Of course it was a play on the old proverb “To err is human; to forgive, divine.” What he meant was that there’s a place for discipline, and it’s often necessary, especially near the beginning of a project. But after discipline has done its work, after it’s gotten us launched, rowing our boat away from land, pushing on the oars, there comes a time when discipline is no longer needed, and the serious joy of the work takes its place.

Read MoreThose who are hypnotized by the grandiose rewards of success tend to berate themselves for not having it yet. When and if they do achieve it, they tend to be the people who forget who they are and get into trouble (addiction, etc.). Those who remember the art and their experience of it—both the acting and the camaraderie of being in a troupe or a cast—tend to cope better with lack of outward success (since the aspect that really matters to them is the one they already do have), and, if things go well, they can tolerate success without losing hold of themselves. Remember: it’s a gift. Humility and gratitude can keep you safe, even in the glare of fame or the darkness of obscurity.

Read More